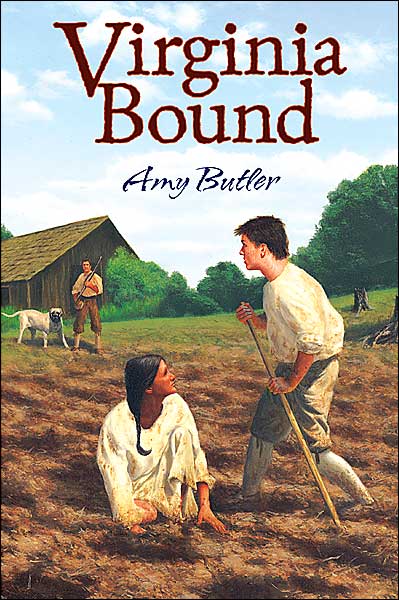

Inspiration for Virginia Bound

Why did you write Virginia Bound?

Years ago, when I was studying for an exam, I ran across a paragraph in an old history book that mentioned how "divers idle yonge people" had been taken off the streets of London and shipped to Virginia as indentured servants in the early 1600s.

I'd never heard of this before, but when I did more research, I discovered that it was true. Hundreds of English orphans, some of them as young as seven years old, were loaded onto ships and sent to Virginia against their will.

Early Virginian records are sparse, so we don't really know much about what became of these orphans. Were they homesick? Were they scared? What happened to them in Virginia?

When I wrote Virginia Bound, I thought about these questions and imagined what the answers might be.

Are the characters in Virginia Bound real?

My characters are imaginary, but the world they live in really did exist. In Virginia Bound, I try to accurately reflect what we know about life in London and Virginia in the 1620s — right down to the clothes people wore, the food they ate, and the laws they had to obey.

To get the details right, I consulted many sources, including recent books and articles, archaeological reports, and maps. I especially enjoyed reading documents written by seventeenth-century people themselves. Their court records, letters, and pamphlets told me many things that I couldn't have found anywhere else.

If you'd like to see some examples of what seventeenth-century people wrote about Virginia, click here.

Did people in early Virginia really talk the way they do in Virginia Bound?

It's very hard to know exactly how people spoke nearly four hundred years ago. Reading Shakespeare, who was writing in the early 1600s, as well as other authors of the time, is helpful, but no one knows for sure exactly how people sounded in everyday street chatter. Moreover, many kids find Shakespearean English very hard to understand. In the end, I used a blend of old and modern English, including Shakespearean words like "gudgeon" (fool) to give the dialogue a seventeenth-century flavor.

To get a sense of how Rob, a Londoner, might have spoken, I read and listened to both modern and historical sources. Although Rob's language doesn't always follow standard modern grammar, it is expressive: "Them ruffians by St. Paul's is a sneaky lot. There's plenty as run afoul of 'em."

The hardest decisions for me as a writer concerned Mattoume's speech. I wanted to avoid the stereotypical and inaccurate Indian speech ("heap big moon tonight") common in many movies and books. This "Tonto talk" understandably offends many Native American Indians.

Knowing this, I planned to render Mattoume's dialogue in fluent English. But as I continued my research on early Virginia, I discovered an awkward fact: in the 1620s the only Virginia Indians who spoke English fluently seem to have been those who had converted to Christianity and were becoming thoroughly assimilated into English society.

The vast majority of Indians resisted this kind of acculturation. By 1627, they had been at war with the English for five years, and they had no wish either to act like Englishman or to sound like them. Indeed, Indians who spoke fluent English were likely to have been seen as pawns of the colonists (and with some justification, since it was at least one and perhaps two of these Anglicized Indians who warned the English about the 1622 uprising, and thus saved the Jamestown colony from destruction).

Given this evidence, I could not in good conscience render Mattoume's dialogue in perfect English. Resistance — even muteness — on her part was far more likely, and far better illustrates Pamunkey courage and tenacity in the face of the English colonial onslaught. While Mattoume does know a little English, and learns more from Rob, she has no desire to make herself sound like an English child. Given the cruel circumstances of her captivity, she has little chance to attain true fluency, but this is not a source of regret for her.

All this research, however, left me in a quandary. I needed to find some way to represent Mattoume's English without making her sound overly fluent or — far worse — resorting to "Tonto talk."

To give a realistic sense of how Mattoume might have spoken, I decided to study the problems encountered by people learning English as a Second Language, and use that as a basis for her speech. Although English is sometimes hard for Mattoume, she is a quick learner — quicker, Rob realizes, than he is himself. She is also a powerful speaker. I am delighted that so many readers admire her intelligence, courage, and strength of character.

Throughout Virginia Bound, I tried as best I could to tell the truth about colonial Virginia, even though I knew the truth would not please everyone. For some, it may be difficult to accept that a Pamunkey girl resisting English capture in 1627 was unlikely to speak fluent English. For others, it may be difficult to accept how brutal early American colonists really were. But I believe that rewriting history to avoid hard truths is deeply dangerous. In the end, we must all face history as it is, not as we would wish it to be, if we want to move honestly towards the future.