Chapter One

The Doll Shop Spy

In 1942, in the middle of World War II, some strange letters came to the attention of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. They were all addressed to the same person in Argentina, and they all sounded oddly alike, yet they came from four different American women. The letters were about dolls, and they ran like this:

I have been so very busy these days, this is the first time I have been over to Seattle for weeks. I came over today to meet my son who is here from Portland on business and to get my little granddaughters doll repaired. I must tell you this amusing story, the wife of an important business associate gave her an Old German bisque Doll dressed in a Hulu Grass skirt . . .

When the FBI questioned the women who supposedly had sent the letters, the women knew nothing about them. FBI lab experts confirmed that the women’s signatures were excellent forgeries.

Someone knew these women well enough to fake their handwriting. Someone was hiding behind their names. Could it be a spy?

The FBI kept digging for clues. The four women lived in different cities and didn’t know each other, but it turned out they had something in common. All of them were long-distance customers of a doll shop at 718 Madison Avenue in New York City.

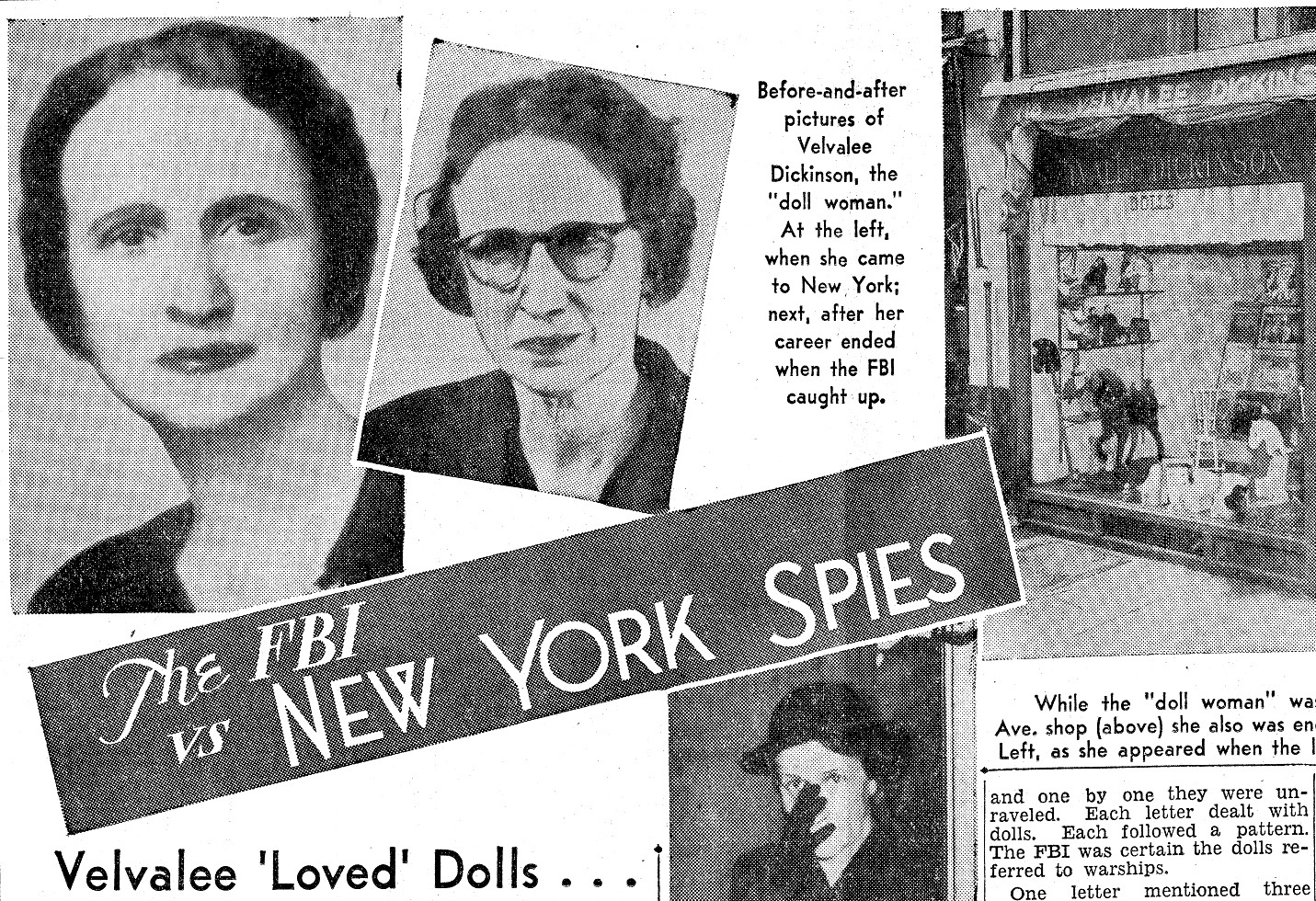

The FBI checked out the shop. Filled with pricey dolls in fancy costumes, it didn’t look like the headquarters of a spy ring. The shop’s owner, Velvalee Dickinson, appeared innocent, too. A graduate of Stanford University, she was a fifty-year-old widow who had been in the doll business since 1937. She and her late husband had once been friends with many Japanese officials, but that was before Japan and the United States had gone to war.

The FBI remained leery. They staked out the doll shop, and they examined Dickinson’s bank account and safe-deposit box. In January 1944, after they traced some of her money back to Japanese sources, they arrested her as a spy.

Dickinson fought back. Tiny, dark-haired, and delicate, she screamed and kicked, scratching at the FBI agents like a wildcat. When they questioned her, she insisted the money had nothing to do with spies. It came from her doll business and insurance payouts.

The FBI was worried. While they’d been able to connect Dickinson to the letters, they weren’t sure how to interpret them. The money trail was also murky, with no clear proof of a link to spymasters. Everything was guesswork, which wouldn’t impress anyone when the case went to trial.

One of the lawyers who had to prosecute the case was assistant U.S. attorney Edward Wallace. He had plenty of courtroom experience, and he knew it was time to seek help. He also knew exactly who he wanted to approach—one of America’s top code breakers, Elizebeth Smith Friedman.

Like Dickinson, Elizebeth was also small, dark-haired, and college-educated, but the resemblance ended there. As a young woman, she had played a key role in code breaking during World War I. She later cracked the codes of American mobsters, smashing their crime gangs. Now, in 1944, she had a top-secret job at the Navy.

Wallace believed that if anyone could crack the Doll Woman letters, it was Elizebeth. But when he asked the FBI if he could put her onto the case, the FBI balked. It wasn’t that they doubted her skill. They had worked with her many times before, so they knew just how good she was. As they saw it, the problem was that Elizebeth was too good. They couldn’t stand the thought that the credit for catching Dickinson might go to her, and not to the FBI.

When it came down to it, however, the FBI needed a conviction. After an initial protest, they allowed Wallace to share the Doll Woman letters with Elizebeth. Luckily for them, the Navy wanted her skills to remain secret, so her name had to be kept out of the record. In case documents, she would be called “Confidential Informant T4.”

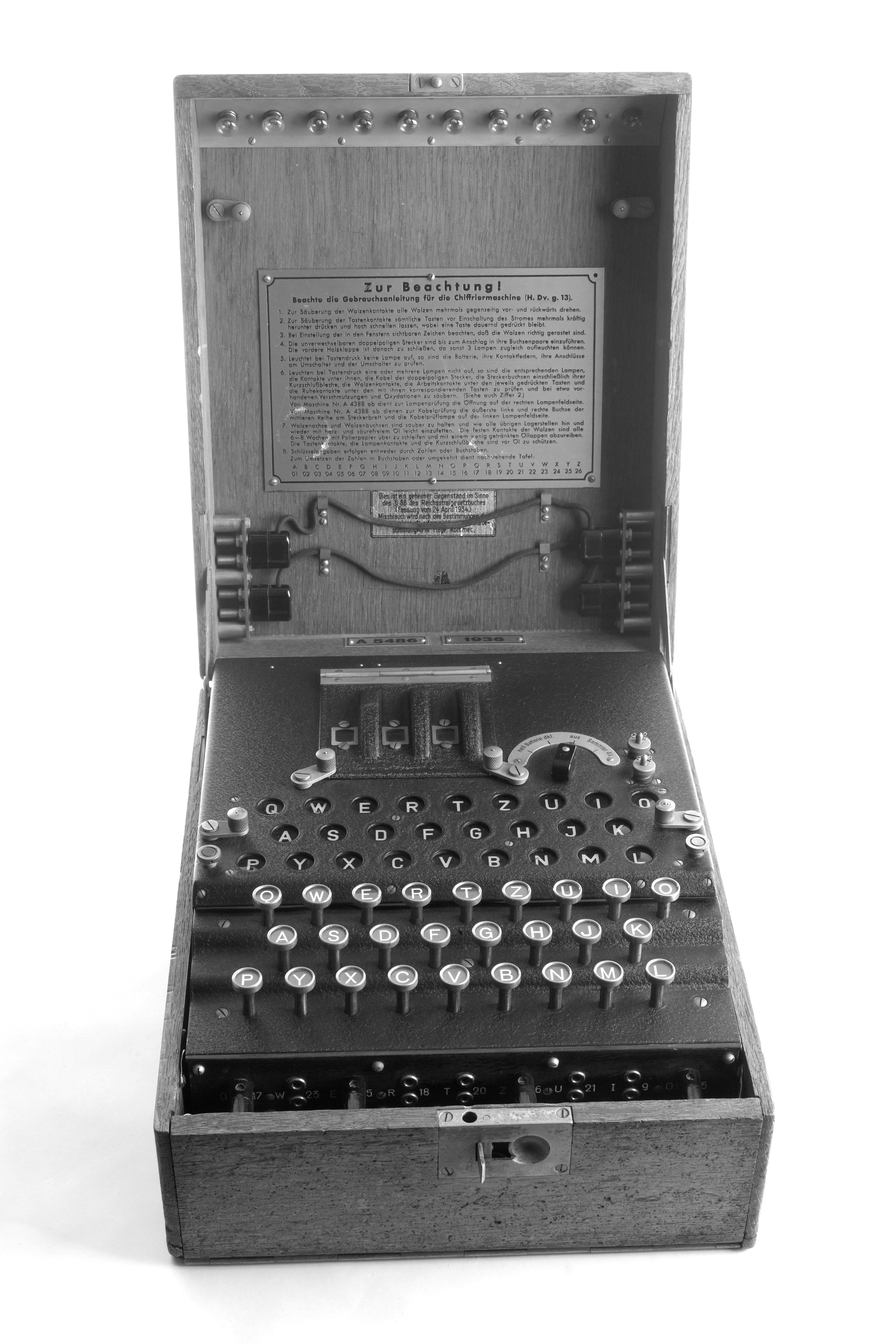

Although Elizebeth was busy tracking Nazi spies, she made time to look at the Doll Woman letters. At first, she was given very little background to go on, but even so she made progress. Soon she was startling everyone with her insights.

As she explained to Wallace, the letters were written in what was called “open code.” This meant that ordinary sentences and phrases had been given secret meanings, agreed upon in advance. These phrases were then strung together in ways that made the letter seem more or less natural to a casual reader.

Elizebeth warned Wallace that the precise meaning of this kind of code was hard to prove. There was usually a certain amount of guesswork involved, and that would make the case hard to prosecute. Yet her analysis was shrewd and hard-hitting.

Take these sentences, for instance, from a Doll Woman letter dated February 22, 1942:

The only new dolls I have are three lovely Irish dolls. One of these three dolls is an old Fisherman with a Net over his back, another is an old woman with wood on her back and the third is a little boy.

Elizebeth believed that Dickinson was using “doll” to mean “ship.” The different dolls stood for different kinds of vessels. The “old Fisherman with a Net” was probably a minesweeper. The “old woman with wood on her back” might be a ship with a high upper deck. The “little boy” could be a small warship, perhaps a destroyer or torpedo boat.

Elizebeth worked out the likely meaning of many other words, too. When the letters mentioned “family,” they referred to either the Japanese fleet or other agents, depending on context. The “visit of important gentleman’s wife” was probably an “invitation to the Japanese Navy to bomb the harbor.” The phrases “Mr. Shaw” and “back to work” were a warning that the USS Shaw, a damaged destroyer, would soon be ready for action again.

Elizebeth also pinpointed phrases that identified Dickinson as a secret agent. She could tell that Dickinson was a layperson where ships were concerned, and she made smart guesses about where and how Dickinson had obtained her information. Elizebeth even found clues indicating who else might be involved in the spy ring.

After she traveled to New York to get additional case details, she was able to say still more about the letters. Her findings were sent to the FBI, and the prosecution used them to strengthen their case. In August 1944, Dickinson was sentenced to ten years of jail time.

The FBI and the newspapers were quick to proclaim that “the War’s No. 1 Woman Spy” had been put behind bars. Elizebeth was not mentioned.

Elizebeth clipped this article that gave the FBI credit for breaking the “Doll Woman” case. In it, Velvalee Dickinson is pictured before and after her arrest (upper left and center).

Elizebeth had mixed feelings about that. For security reasons, she knew she had to stay out of the limelight. If the Nazis ever learned how good she was at code breaking, it would hamper her efforts to bring their spies down. But it annoyed her to see the FBI taking credit for her work.

It wasn’t the first time that Elizebeth had been pushed into the shadows, nor was it the last. On the FBI’s public website, the account of the Doll Woman case still omits any mention of her, even though the need for secrecy is long past. Married to William Friedman, one of the best code breakers of all time, she is often mentioned merely as his wife. Yet as William himself was quick to point out, Elizebeth was brilliant, too.

Like the open code in Dickinson’s letters, Elizebeth could appear ordinary on the surface. Even now, she is easily underestimated. To get her true measure, you must delve deeper, the way a code breaker would, searching for the truth that lies just out of sight.

Elizebeth did not have an easy start in life. Yet she rose to become one of the most formidable code breakers in the world, the scourge of gangsters and spies. How did she do it? Ambition and grit played a part, but she needed opportunity, too.

She found it in a library—and in one of the strangest job offers of the century.

Chapter Two

Starting Out

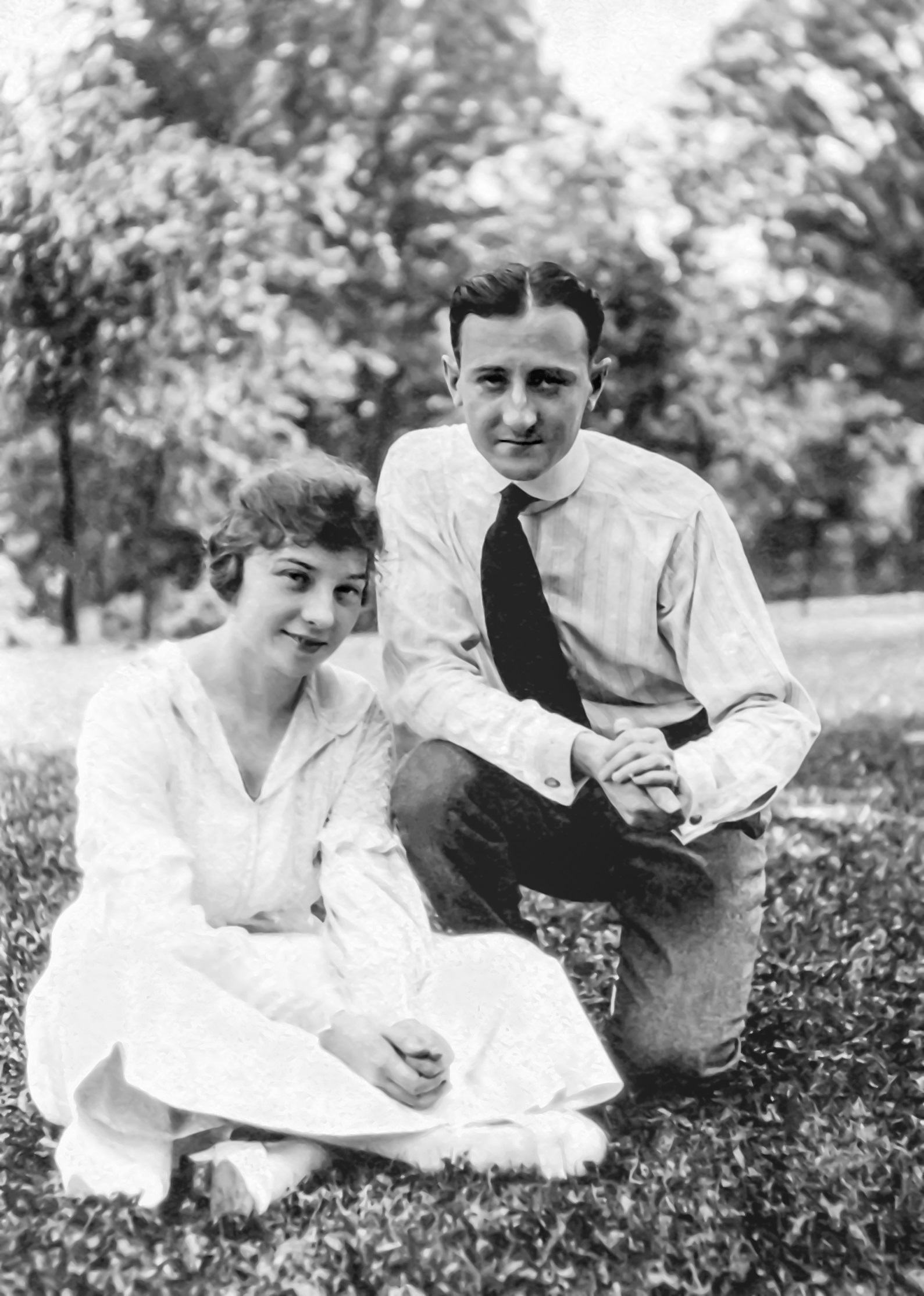

Elizebeth rarely talked about what her life was like before she became a code breaker. She didn’t save much from those early years, either. Look in her files, and you’ll find only a few papers, a slim diary, and a handful of old photos from that time. It was a chapter of her life that she kept to herself.

To discover who she was when she started out, you have to comb through all the evidence she left behind, and then go hunt for more. A faded few lines on a census form. A remark made in jest. An old house that still stands square to the road. Like scattered bits of code, none of these snippets gives away much on its own. But piece them together, and the real story starts to emerge.

What you see, early on, is that young Elizebeth Smith was determined to be different. Sensitive to the weight and meaning of letters and words, she wanted even her name to set her apart. There was nothing she could do about her surname—the “odious name of Smith,” as she put it in her college diary. Yet she detested that “most meaningless of phrases, ‘plain Miss Smith.’” To her mind, it implied that she was “eliminated from any category even approaching anything interesting.”

It must have been a comfort that her first name was unusual, if only in its spelling. Her mother, Sopha Strock Smith, had called her Clara Elizebeth. It was the Elizebeth part that stuck, spelled with an “e” in the middle, rather than with the standard “a.” Family legend had it that Sopha wanted to avoid the nickname Eliza. Perhaps it was also her way of encouraging Elizebeth to stand out from the crowd.

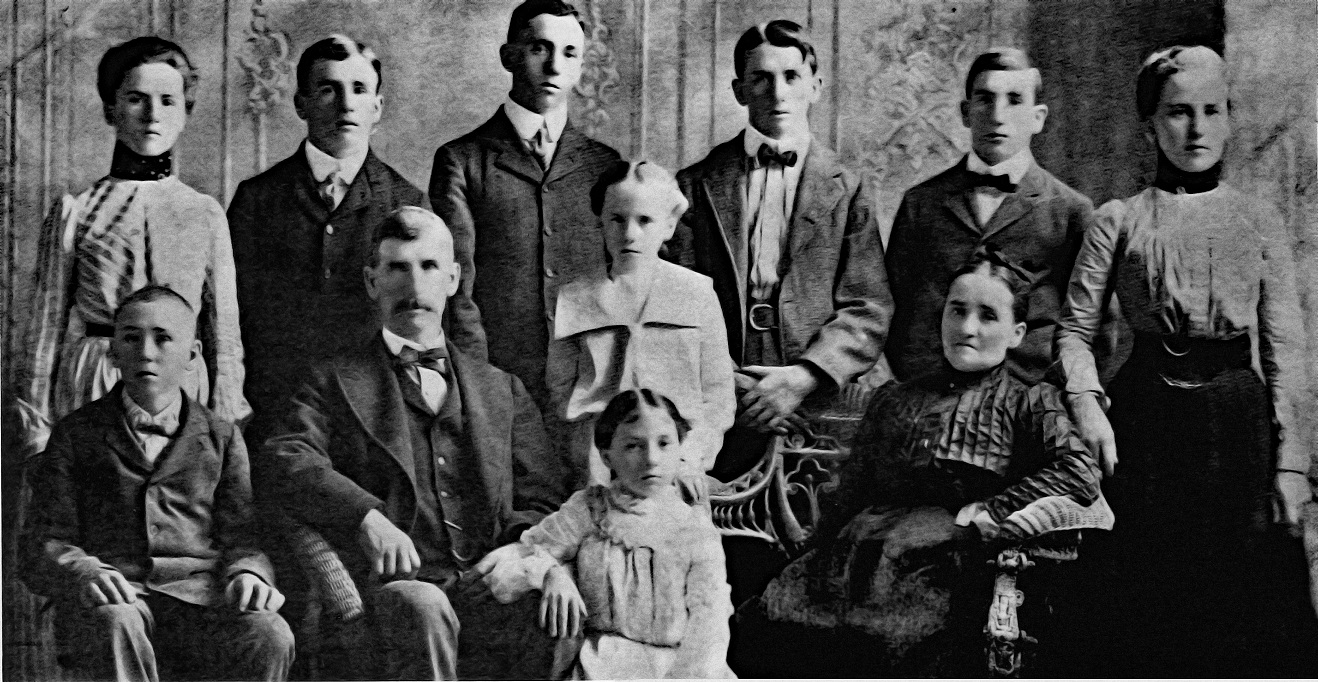

Sopha was Elizebeth’s champion—and Elizebeth certainly needed one. Born on August 26, 1892, she was Sopha’s youngest surviving child, with eight older brothers and sisters. They all lived in a brick house that Elizebeth’s grandfather had built, on the Smith family farm in Union Township, a few miles east of Huntington, Indiana.

Delicate by nature, with wavy brown hair and hazel eyes, Elizebeth was a tiny presence in that huge family. It was a position that frustrated her. Prone to nausea and stomach problems, she remembered her early years as “as one continual period of throwing up.”

A portrait of the Smith family, with Elizebeth sitting front and center.

Home was a tense place because Elizebeth and her father did not get along. John Marion Smith had served in the Union Army as a teenager, marching with General Sherman in the Civil War. The experience had soured him, but he was widely respected as a veteran and a good farmer. A staunch Republican, he was also elected to local office. By nature, he was a rigid and controlling man, and he did not think much of females. Sopha tried to shield Elizebeth from his temper.

To Elizebeth, Sopha was her “wonderful little Mother”—a smart and curious woman who was interested in everyone. Like Elizebeth, Sopha was small and dark-haired, and she too had been the youngest child in her family. Educated at one of the most advanced schools in rural Indiana, she became a teacher. After she married John Smithwhen she was twenty-four, she centered her life around family and church, yet she often told fond stories about her student days.

Most likely, it was Sopha who spurred Elizebeth to get a good education. She also gave her daughter backbone. “My mother encouraged me to go my own way,” Elizebeth once said—a lesson that stayed with her for life.

The Smith Family Farmhouse.

Elizebeth had a quick mind, and she did well in her studies. At first, she walked to the small Antioch School near the family farm. Later, she and her parents moved into nearby Huntington, where she went to high school. Drawn to words in any language, she took four years of German and five years of Latin. She had a strong voice despite her small frame, and she spoke with “rare force and effectiveness,” winning the class orator prize. At a time when nine out of ten students never even graduated from high school, she was aiming at college.

Her father did not approve. Believing that higher education was a waste of time for girls, he refused to pay a penny toward it.

To get around this, Elizebeth applied for a scholarship to Wellesley. She also applied to Swarthmore, and perhaps Earlham, another Quaker college, as well. Some people have taken this as proof that she herself was Quaker, but the real story is more complicated—and it shows that Elizebeth was willing to use every lever to get an education. Her parents were pillars of the local Church of God, and that was the faith she was raised in. But she knew that her father came from Quaker stock, and that he was proud of his forebears. If she could get into a Quaker college, she hoped his pride would prompt him to help pay her costs.

Her well-crafted plans fell apart. She failed to get into Wellesley or Swarthmore. Earlham did not work out, either, perhaps because her father was unwilling to help her. At her graduation in 1910, she had the second-highest GPA in her class, and she stated that she had college plans. Instead, she spent the next year at home, playing piano for church socials.

It was such a dismal year that she tried to erase it from her memory, pretending it had never happened. Later, she would always subtract one year from her age, as if to say that her extra year at home hadn’t counted. But if her father thought she would give up on college, he was wrong. She applied again that year.

This time around, she was accepted at the College of Wooster in Ohio. It had no Quaker links whatsoever, but somehow she managed to talk her father into giving her a loan anyway. Still, he drove a hard bargain. She had to pay back every penny, plus six percent extra for interest.

Elizebeth thought it a price worth paying.

At college, she took classes in English, Greek, and philosophy. She studied poetry and the plays of William Shakespeare, and she wrote poems of her own. No longer under her father’s thumb, she enjoyed thinking for herself. “I am never quite so gleeful as when I am doing something labeled as an ‘ought not’!” she confessed to her diary. She wondered if this rebellious streak was the reason why “so many people remark that I should have been born a man.”

Yet even with her father’s money, she struggled to get by. To make enough to live on, she sewed clothes and arranged hair for parties. The work wearied her and made her feel “indigo, Prussian, navy, blue.” It was hard to keep up with her studies when she had to “make dresses and comb hair for other folks.” The sense that she wasn’t living up to her potential gnawed at her.

Elizebeth as a teenager.

Other things bothered her, too. A stickler for accuracy, she believed in plain speaking. Attempts to beat around the bush made her turn prickly. She had strong opinions, and she wasn’t afraid to defend them. But young women who spoke their minds were not always welcome, even at college, and at times she found herself seething with frustration.

In Huntington, where she spent her summers, she felt even worse. “I hate the place,” she wrote in 1913. She felt boxed in by the town and by neighbors who didn’t approve of her. Most of all, she felt misunderstood by her own family, who scolded her for being touchy and outspoken and having a bad attitude.

Looking for comfort, she went to visit old friends in the country. It soothed her to sleep “out under the stars,” to row over flooded farmland, and to paddle a canoe. Music helped, too. One night her “heart was carried completely away by a baritone. . . . It made me want to be able to sing well myself, so badly that—well, I just couldn’t sit still with the desire of it.”

In the fall of 1913, Elizebeth transferred to Hillsdale College in Michigan. Later in life, she said that this was because her mother was ill. Her family thought it had more to do with a “romance gone wrong,” but the truth has been lost to time. Whatever lay behind the move, she soon regretted it. The rebel inside her was hard to satisfy, and she found it difficult to settle. “I wanted, oh so badly, to come here; and disregarded my mother’s wishes, and paid a big price to come,” she confided to her diary. “Now it all seems so worthless and useless.”

Honesty forced her to admit that the move had made her more discontented, not less. But in time, she hit her stride. She became literary editor of the college paper, joined the sorority Pi Beta Phi, and was even elected class president. She also fell hard for a handsome, moody poet named Harold Van Kirk. Known as Van, he had started off as a student minister, but he soon found his true calling in theater. He called her Betty and sent her French sonnets, as well as ardent lines about midnight meetings, written in a bold, dashing hand.

In 1915, Elizebeth finally earned her B.A. degree. And that’s when her life took a wrong turn.

***

As soon as Elizebeth finished college, she had to start repaying the loan from her father. It was $600 in all, a hefty sum in 1915—plus the surcharge for interest. She felt the weight of it like a millstone around her neck, dragging her down. She knew it would take her years to pay it all off.

The debt meant that she needed to get a job right away. Her first thought was business. Had she been a man, she probably would have had her pick of positions, but at the time few workplaces welcomed women. Teaching was often the only option for female college graduates, and that’s how it played out for Elizebeth. She took one of the few openings she could find: substitute high school principal in a small Indiana townnear her home. The job didn’t suit her, and in 1916 she quit.

By then, she was in the midst of a full-blown crisis.

It wasn’t just the job that had gone wrong. “I had broken my engagement,” she later wrote of that time. Her “fiancé–gone astray” was the poet Van. After she earned her degree, Van had visited her in Huntington, spending time with her family as any serious suitor would. But he was younger than she was, so in the fall he had returned to Hillsdale and the fun of college life. That likely put a strain on the relationship, though the exact reasons for the breakup aren’t clear.

She didn’t know it, but she’d had a lucky escape. Van never lost his way with women, and he later married and divorced at least two heiresses. But he turned out to be a liar and a cheat, and he had a vicious streak. Even his children had nothing good to say about him.

At the time, however, the rift with Van made Elizebeth feel desolate. So did the thought of another “run-of-the-mill” teaching job. Yet how else could she pay back the loan?

She found herself facing the future with dread, seeing only “a long stretch of purposeless years with nothing to live for.” She feared she would spend her life all alone, chained to jobs she hated, marking papers and marking time. Her feelings were so raw, and her hopes so broken, that she found herself “wish[ing] passionately day after day only to die.”

As long as she was alive, however, she needed to pay back her father. So in May 1916, she started to look for work again. Desperate for a fresh start, she boarded a train to Chicago.

There a library visit sent her life spinning in a whole new direction.